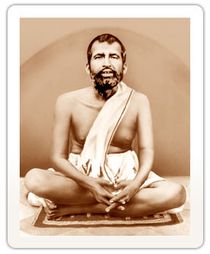

Sri Ramakrishna - A short life

(1836-1886)

Sri Ramakrishna was

born in a village called Kamarpukur in the district of Hugli (Bengal) on Wednesday, the 18th of February 1836. He came of a highly respected, though poor, Brahmin family.

Sri Ramakrishna's father, Khudiram Chatterjee, was a great devotee. His mother Chandramani Devi was the personification of kindness. In her there was no guile.

Sri Ramakrishna was called Gadadhar in his childhood. He received some lessons in reading, writing and arithmetic at the village primary school.

After leaving the village school, the boy was not allowed to sit idle at home. His next duty was to attend to the daily worship of his household God Raghuvir. Every morning he chanted the name of

the Lord, put on a holy garment, and gathered flowers. After ablutions, prayers and meditation on the Supreme Being, the One and Indivisible God, he worshipped Raghuvir, also called Rama, one of

the Incarnations of the Supreme Being, and the Hero of the well-known epic, the Ramayana. He could sing divinely. The songs that he heard during theatrical performances, he could recite from

beginning to end. From a boy, he was always happy. Men, women and children - everybody loved him.

Brahmin scholars were often, as is the practice amongst the Hindus, engaged to read from the Sacred Books about the Life and Teachings of the various Incarnations of God, and sing and narrate the

incidents in the vernacular. Sri Ramakrishna would listen to these men with rapt attention. In this way he mastered the Ramayana, the Mahabharata and the Bhagavata - all religious epics relating

to Rama and Krishna who are both regarded by the Hindus as Incarnations of God.

When eleven years old, Sri Ramakrishna was one day going through the corn-fields to Anur, a village near Kamarpukur. As he told his disciples afterwards, he suddenly saw a Vision of Glory and

lost all sense-consciousness. People said, it was a fainting fit; but it was really that calm and serene mood, that superconscious state, called Samadhi, brought on by God-vision.

After the death of his father, Sri Ramakrishna, then seventeen or eighteen years old, went with his elder brother to Calcutta. The brothers came down to Calcutta with an intention of seeking

their fortune.

Rani Rashmani, a rich and pious Bengali lady, built the well-known temple at Dakshineswar, a village about four miles from Calcutta, in 1855 A.D. The eldest brother of Sri Ramakrishna Pandit Ram

Kumar, was appointed the chief priest of the temple of Mother Kali, the Goddess.

Sri Ramakrishna used often to come to the temple to see his brother. Within a few days he was himself employed as an assistant priest.

In the course of a few days a change came over Sri Ramakrishna. He was found sitting alone for long hours before the Image of the Mother. Evidently his mind was drawn away from things of this

world. It was in quest of some Object not sought by men of the world.

His people shortly arranged his marriage. They hoped that marriage would turn his mind away from his Ideal World. But the marriage had been only in name. His newly married bride Sri Sri

Saradamani Devi was also an illumined soul of the highest order. After his marriage Sri Ramakrishna returned to the temple-garden at Dakshineswar. This was the turning point of his godly life. In

a few days, while worshipping the Mother, he saw strange Visions of Divine Forms.

It was soon found by the temple authorities that Sri Ramakrishna was, in the present state of his religious feelings, incapable of doing the duty of a priest any longer. Nor could he go on doing

his duties as a householder. He said 'Mother, O ! Mother !' night and day.

There was a guest-house in the Temple-garden. Holy men who had given up the world used to come there as guests. Tota Puri, a holy man, stayed there as a guest for eleven months. He it was who

expounded to Sri Ramakrishna, the Vedanta philosophy. During the exposition Tota observed that his disciple was no ordinary man, and that he frequently went into a state of Divine Ecstasy in

which the finite ego goes out of sight and becomes one with God,' the Universal Ego!

A Brahmin lady who had also given up the world came as a guest to the Temple a little before Tota Puri. She it was who helped Sri Ramakrishna to go through the practices enjoined by the

Scriptures called the Tantras.

He used to pass through three different states of religious consciousness viz., the purely Internal or Super-consciousness State, in which there can be no outward consciousness; the

Half-conscious State in which outward perception is not entirely lost; and the Conscious State in which it is possible for one to chant the holy name of the Lord. With 'Mother, O! Mother!' ever

on his lips, he would talk to the Divine Mother without cessation. He would ask Her to teach him. He would often say, 'O Mother, I know not the Sacred Books; nor have I anything to do with the

pandits well versed in them. It is Thou alone whose words I shall hear. Teach Thou and let me learn.'

The sweet name of Mother, Sri Ramakrishna applied to the Supreme Being, God the Absolute, who transcends all thought, all time and space.

Besides teaching the fact that God may be seen, his great object was to point out the harmony amongst all religions. He realised, on the one hand, the Ideal set up by each of the various sects of

the Hindu religion, and on the other, the Ideal of Islam and that of Christianity. He recited in solitude the name of Allah and meditated upon Jesus Christ. In a vision he saw Jesus in his glory.

In his chamber he made room for the pictures not only of Hindu Gods and Goddesses including Buddha, but also for that of Jesus.

He looked upon all women as incarnations of the Divine Mother and he worshipped them as such.

Ramakrishna fell sick with cancer in the throat in 1885. He was removed to Cossipore for treatment. By now he had come to be known as a great religious teacher. Many of the Calcutta elite came

under his influence, but Ramakrishna was not satisfied until he had a band of young men who were prepared to mould themselves strictly according to his instructions. Such young men came, fifteen

or sixteen in number, all with a good family background, and modern education. All of them are now well-known, for their later achievements as religious teachers, most of all their leader Swami

Vivekananda, who in fact influenced every aspect of Indian national life. It is this band of young men who later formed the Ramakrishna Order.

Many are those who have become and are becoming his followers to-day. The family of his disciples lies scattered to-day not only in Asia including Japan, but also in America and Europe.

Sri Ramakrishna entered into Mahasamadhi in Cossipor Gardens House near Calcutta on 16 August, 1886.

Sayings of Sri Ramakrishna:

God is formless and God is possessed of form too. And He is also that which transcends both form and formlessness. He alone knows what all He is. For the sake of those that love the Lord, He

manifests Himself in various ways and in various forms. Verily He is not bound by any limitation as to the forms of manifestation, or their negation.

It is not good to feel that one's own religion alone is true and all others are false. God is one only, and not two. Different people call on Him by different names: some as Allah, some as God,

and others as Krishna, Siva, and Brahman. It is like the water in a lake. Some drink it at one place and call it 'jal', others at another place and call it 'pani', and still others at a third

place and call it 'water'. The Hindus call it 'jal', the Christians 'water', and the Mussalmans 'pani'. But it is one and the same thing. Opinions are but paths. Each religion is only a path

leading to God, as rivers come from different directions and ultimately become one in the one ocean.

If I hold this cloth before me, you cannot see me any more, though I am still as near to you as ever. So also, though God is nearer to you than anything else, yet by reason of the screen of

egoism you cannot see Him.

If, after all, you cannot destroy this "I" then let it remain as " I the servant". The self that knows itself as the servant and lover of God will do little mischief.

When shall I be free? -- When that "I" has vanished. "I and mine" is ignorance; "Thou and Thine" is knowledge.

The intoxication of the hemp is not to be had by repeating the word "hemp". Get the hemp, rub it with water into a solution and drink it, and you will get intoxicated. What is the use of loudly

crying, "O God, O God !" ? Regularly practise devotion and you shall see God.

As the tiger devours other animals so does the 'tiger of zeal for the Lord' eat up lust, anger, and the other passions. Once this zeal grows in the heart, lust and the other passions

disappear.

The darkness of centuries is dispersed so soon as a single light is brought into the room. The accumulated ignorance and misdoings of innumerable births vanish at one glance of the gracious eyes

of God.

The nearer you come to God, the more you feel peace. Peace, peace, peace-supreme peace! The nearer you come to the Ganges, the more you feel its coolness. You will feel completely soothed when

you plunge into the river.

Pray to Him in any way you will. He is sure to hear you, for He hears even the footfall of an ant.

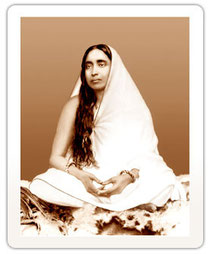

Sri Sarada Devi - A short life

(1853-1920)

Rumours spread to

Kamarpukur that Ramakrishna had turned mad as a result of the over-taxing spiritual exercises he had been going through at Dakshineswar. Alarmed, Chandra Devi brought him home and arranged that he might have the best medical care available in

their village. The doctors who examined him declared that there was nothing abnormal about him. Chandra Devi who studied him closely also found he was absolutely normal. As he had always

done, Ramakrishna sang songs, told stories, cut jokes and made people laugh. That is all. He was interested in everything except in the financial affairs of the family.

Chandra Devi's neighbours advised that if Ramakrishna could be persuaded to marry, he might then be more conscious of his responsibilities to the family and accordingly pay more attention to

its financial needs. Chandra Devi started looking for a suitable bride. She did not want Ramakrishna to know anything about her plan , for she feared that he might see marriage as a hindrance

to his spiritual progress. Ramakrishna, however, came to know, and far from objecting to the marriage, began to take an active interest in the selection of the bride. He, in fact, mentioned

Jayrambati, three miles to the north-west of Kamarpukur, as being the village where the bride could be found at the house of one Ramchandra Mukherjee. The bride, six-year old and bearing the

name, Sarada, was found. The marriage was duly solemnized in 1859; the bride went back to her father's house and Ramakrishna to Dakshineswar to resume his spiritual practices.

Years passed and the bride and the bridegroom seldom met. Sarada continued to live at her father's house, helping her poor peasant parents with the usual chores of feeding the cattle,

carrying food to the paddy-fields for labourers working for her parents, cooking, cleaning, looking after the younger brothers, and so on. Once famine gripped Jayrambati and its surrounding

areas. Starving people went about searching for food, but there was no food anywhere. It so happened that Sarada's parents had saved some food grains that year. They decided to cook some food

everyday and distribute it to the starving people, fresh and hot. Sometimes, the hungry people would burn their fingers in eating hot food. Sarada, still a tiny girl, would fan the food to

help it cool. She did it on her own.

As Sarada grew older. neighbours began to gossip about her misfortune. They would say that her husband had gone mad. Sarada overheard such remarks and was naturally very disturbed. She

decided to go to Dakshineswar and see for herself the condition of her husband. She went and found her husband quite normal. She stayed with him for some time and then returned to Jayrambati.

After some years, she permanently stayed with him .

In a way, Sarada Devi was Ramakrishna's first disciple. He taught her as much religion as philosophy. He taught her everything he had learnt from his various Gurus. Ramakrishna must have been

pleased to see that she mastered every religious secret as quickly as he himself had done, perhaps even more quickly. Impressed by her great religious potential, he began to treat her as the

Universal Mother Herself. Once she asked him what he thought of her. He said, 'I look upon you as my own mother and as the Mother who is in the temple.'

Before passing away, in 1886, Ramakrishna made Sarada Devi feel as if she was the mother of his disciples, nay of the entire humanity. At first, Sarada Devi was shy about playing this role,

but slowly, she filled that role, and even became a religious teacher in her own rights.

For the thirty-four years or so that she lived after Ramakrishna's passing away, she inspired people, both monastic and lay, with the ideals that Ramakrishna himself had preached and

practised. She did this in the same way as Ramakrishna - she lived those ideals. But her life was more testing and complicated than Ramakrishna's. Being an ideal monk, Ramakrishna always kept

away from the cross-currents of a family life. He loved to watch the fun called life but was careful enough never to be drawn into its maelstroms. Sarada Devi, on the contrary, was at the

very heart of it. She was the head of a large family comprising men and women, most of them not even distantly related to her. And what an assortment of characters they were! Some of them

were great souls by any standard, but there were also some who were mean, jealous, and positively mischievous. She managed to keep them all together without losing her balance of mind. And

each of them was convinced that she loved him or her the best. They were all of them dependent on her, not only spiritually but also materially. She was not only their 'mother' but also their

guru. She gave them full satisfaction on both scores.

Sarada Devi had a hard life from beginning to end. As daughter, wife, and finally, as the beloved mother of a large community of people cutting across race and language, there were demands on

her much more than a woman in her circumstances normally has to meet. She fulfilled them in a manner possible only for her. But what is remarkable is that, in the midst of all her cares, she

maintained a degree of aloofness which Hinduism attributes to the highest and best among men and women. Through the skein of the varying situations which she faced, she remained absolutely

calm and equipoised as if these were no concern of hers. Her fortitude, courage, and wisdom, tested again and again, amazed everybody.

But the most amazing thing about her was her renunciation. a quality she shared with her husband in a measure equal to, if not more than, his. She often found herself in a situation in which

starvation seemed certain, but under no circumstances would she seek aid from any quarter. Even when her disciples had grown to a considerable number and there were people among them with

means to keep her in comfort and also anxious to be of service to her, she would never so far as even drop a hint that she had any difficulty or she had any hankering.

But the trait of her personality, which used to draw innumerabable people, men and women, good and bad, rich and poor, young and old fowards her irresistibly was her Universal Motherhood. She

would often say, 'I am as much the Mother of the good as of the bad. ...I shan't be able to turn away anybody if he addresses me as Mother...If my son wallows in the dust or mud, it is I who

have to wipe all the dirt off his body and take him to my lap.'

She taught not by precepts but by examples. There were irritants galore in the way people around her behaved, but she was an indulgent mother who knew the best way to educate an erring child

was to set an example before him, which she did. She had seen the worst side of man, but she never lost faith in him, knowing that, given affection, sympathy, and guidance, he could overcome

all his limitations.

She was human, yet divine. Her divinity shone through everything she did, even if it was something entirely mundane. She was a simple woman, but in thought, speech, and action she was attuned

to God. She was a true saint, but she never claimed she was. She passed as an ordinary woman, but everything about her was extraordinary.

Sayings of Sri Sarada Devi:

You see, it is the nature of water to flow downwards, but the sun's rays lift it up towards the sky; likewise it is the very nature of mind to go to lower things, to objects of enjoyments,

but the grace of God can make the mind go towards higher objects.

One must perform work. It is only through work that the bondage of work will be cut asunder and one will get a spirit of non-attachment. One should not be without work even for a

moment.

Many are known to do great works under the stress of some strong emotion. But a man's true nature is known from the manner in which he does his insignificant daily task.

Everything depends upon one's mind. Nothing can be achieved without purity of mind. It is said, "The aspirant might have received the grace of the Guru, the Lord and His devotees; but he

comes to grief without the grace of 'one'." That 'one' is the mind. The mind of the aspirant must be gracious to him.

From desire comes this body into being. When there is no desire at all, the body falls away. With complete cessation of desire there comes the final end.

Just as clouds are blown away by the wind, so the thirst for material pleasure will be driven away by the utterance of the Lord's name.

There is no happiness whatever in human birth. The world is verily filled with misery. Happiness here is only a name. He on whom the grace of the Master has fallen alone knows him to be God

Himself. And remember that is the only happiness.

Practise

meditation, and by and by your mind will be so calm and fixed that you will find it hard to keep away from meditation.

If you pray to him (Sri Ramakrishna) constantly before his picture then he manifests himself through that picture. The place where that picture is kept becomes a shrine.

The easiest and best way of solving the problems of life is to take the name of God, of Sri Ramakrishna, in silence.

Swami Vivekananda - A short life

(1863-1902)

Swami Vivekananda had been born in Calcutta on 12th January 1863. The name of

his family was Datta, and his parents gave him the name Narendranath; Naren for short.

When Naren was in his middle teens, he started going to college in Calcutta. He was a good-looking, athletic youth and extremely intelligent. He was also a fine singer and could play several

musical instruments. Already, he showed a great power for leadership among the boys of his own age. His teachers felt sure that he was destined to make a mark on life.

In November 1881, he was invited to sing at a house where Ramakrishna was a guest. They had a brief conversation and Ramakrishna invited the young man to come and visit him at the

Dakshineswar Temple, on the Ganga a few miles outside Calcutta, where he lived.

From the first, Naren was intrigued and puzzled by Ramakrishna's personality. He had never met anyone quite like this slender, bearded man in his middle forties who had the innocent

directness of a child. He had about him an air of intense delight, and he was perpetually crying aloud or bursting into song to express his joy, his joy in God, the Mother Kali, who evidently

existed for him as live presence. Ramakrishna's talk was a blend of philosophical subtlety and homely parable. He spoke with a slight stammer, in the dialect of his native Bengal village, and

sometimes used coarse farmyard words with the simple frankness of a peasant.

For Ramakrishna, in his almost unimaginably high state of spiritual consciousness, Samadhi was a daily experience, and the awareness of God's presence never left him. Vivekananda recalls

that, "I crept near him and asked him the question I had been asking others all my life: 'Do you believe in God, sir?' 'Yes,' he replied. 'Can you prove it, sir?' 'Yes.' 'How?' 'Because I see

Him just as I see you here, only much more intensely.' That impressed me at once. For the first time, I found a man who dared to say that he saw God, that religion was a reality - to be felt,

to be sensed in an infinitely more intense way than we can sense the world."

After this, Naren became a frequent visitor to Dakshineswar. He found himself gradually drawn into the circle of youthful disciples - most of them about his own age - whom Ramakrishna was

training to follow the monastic life.

In 1885 Ramakrishna developed cancer of the throat. As it became increasingly evident that their Master would not be with them much longer, the young disciples drew more and more closely

together. Naren was their leader.

On 15th August 1886, Ramakrishna uttered the name of Kali in clear ringing voice and passed into final Samadhi.

The boys felt that they must hold together, and a devotee found them a house at Baranagore, about halfway between Calcutta and Dakshineswar, which they could use for their monastery.

But gradually the boys became restless for the life of the wandering monk. With staff and begging bowl, they wandered all over India, visiting shrines and places of pilgrimage, preaching,

begging, passing months of meditation in lonely huts. Sometimes they were entertained by Rajas or wealthy devotees; much more often, they shared the food of the very poor.

Such experiences were particularly valuable to Naren. During the years 1890-93 he acquired the firsthand knowledge of India.

At the end of May 1893 he sailed from Bombay, via Hong Kong and Japan, to Vancouver; from there he went on by train to Chicago, to join the Parliament of Religions to be held on 11 September,

1893.

This was probably the first time in the history of the world that representatives of all major religions had been brought together in one place, with freedom to express their beliefs. But

Swamiji had no formal invitation to join the Parliament as a delegate. But Professor J. H. Wright of Harvard University assured him that he would be welcome at the Parliament even though he

had no formal invitation: "To ask you, Swami, for credentials," the Professor remarked, "is like asking the sun if it has permission to shine."

When the Parliament opened, on the morning of 11th September, Vivekananda immediately attracted notice as one of the most striking figures seated on the platform, with his splendid robe,

yellow turban, and handsome bronze face.

During the afternoon, Vivekananda rose to his feet. In his deep voice, he began, "Sisters and Brothers of America" - and the entire audience, many hundred people, clapped and cheered wildly

for two whole minutes. A large gathering has its own strange kind of subconscious telepathy, and this one must have been somehow aware that it was in the presence of that most unusual of all

beings, a man whose words express exactly what he is. When Vivekananda said, "Sisters and Brothers", he actually meant that he regarded the American women and men before him as his sisters

and brothers: the well-worn oratorical phrase became simple truth.

As soon as they would let him, the Swami continued his speech. It was quite a short one, pleading for universal tolerance and stressing the common basis of all religions. When it was over,

there was more, thunderous applause.

After the closing of the Parliament of Religions, Vivekananda spent nearly two whole years lecturing in various parts of the eastern and central United States.

He met and made an impression on people of a more serious kind-Robert Ingersoll the agnostic, Nikola Tesla the inventor, Madam Calve the singer, and most important of all, he attracted a few

students whose interest and enthusiasm were not temporary; who were prepared to dedicate the rest of their lives to the practice of his teaching.

He had a message to the West. He asked his hearers to forsake their materialism and learn from the ancient spirituality of the Hindus. What he was working for was an exchange of values. He

recognised great virtues in the West - energy and initiative and courage - which he found lacking among Indians.

Vivekananda taught that God is within each one of us, and that each one of us was born to rediscover his own God-nature.

In August he sailed for France and England, and preached Vedanta, returning to New York in December. It was then that, at the urgent request of his devotees, he founded the first of the

Vedanta Societies in America: the Vedanta Society of New York. (Vedanta means the non-dualistic philosophy which is expounded in the Vedas, the most ancient of Hindu scriptures.)

Vivekananda landed in Ceylon in the middle of January 1897. From there on, his journey to Calcutta was a triumphal progress. His countrymen had followed the accounts of his American lectures

in the newspapers.

Indeed, one may claim that no Indian before Vivekananda had ever made Americans and Englishmen accept him on such terms - not as a subservient ally, not as an avowed opponent, but as a

sincere well-wisher and friend, equally ready to teach and to learn, to ask for and to offer help. Who else had stood, as he stood, impartially between East and West, prizing the virtues and

condemning the defects of both cultures?

On 1st May 1897, he called a meeting of the monastic and householder disciples of Ramakrishna in Calcutta in order to establish their work on an organized basis. What Vivekananda proposed was

an integration of educational, philanthropic, and religious activities; and it was thus that the Ramakrishna Mission and the Ramakrishna Math, or monastery, came into existence. The Mission

went to work immediately, taking part in famine and plague relief and founding its first hospitals and schools.

The Math was consecrated some time later, at Belur, a short distance downriver from Dakshineswar Temple, on the opposite bank of the Ganga. This Belur Math is still the chief monastery of the

Ramakrishna Order, which now has 135 centres in different parts of India and the world including Japan, Europe and America, devoted either to the contemplative life or to social service, or

to a combination of both. The Ramakrishna Mission has its own hospitals and dispensaries, its own colleges and high schools, industrial and agricultural schools, libraries and publishing

houses, with monks of the Order in charge of them.

In June 1899, Vivekananda sailed for a second visit to the Western world.

By the time he returned to India, Vivekananda was a very sick man; he had said himself that he did not expect to live much longer.

Vivekananda' entered into Mahasamadhi in Belur Math on 4 July 1902.

The best introduction to Vivekananda is not, however, to read about him but to read him. The Swami's personality, with all its charm and force, its courageousness, its spiritual authority,

its fury and its fun, comes through to you very strongly in his writing and recorded words.

Vivekananda was not only a great teacher with an international message; he was also a very great Indian, a patriot and an inspirer of his countrymen down to the present generation.

You can visit that room in Belur Math, India, in which Swamiji lived; it is still kept exactly as Vivekananda left it.

Sayings of Swami Vivekananda:

The remedy for weakness is not brooding over weakness, but thinking of strength. Teach men of the strength that is already within them.

If you have faith in the three hundred and thirty millions of your mythological gods, and in all gods which foreigners have introduced into your midst, and still have no faith in yourselves, there is no salvation for you. Have faith in yourselves and stand up on that faith.

Unselfishness is more paying, only people have not the patience to practise it.

This life is short, the vanities of the world are transient, but they alone live who live for others, the rest are more dead than alive.

As I grow older I find that I look more and more for greatness in little things. Anyone will be great in a great position. Even the coward will grow brave in the glare of the footlights. The world looks on! More and more the true greatness seems to me that of the worm doing its duty silently, steadily from moment to moment and hour to hour.

Can religion really accomplish anything? It can. It brings to man eternal life. It has made man what he is and will make of this human animal, a God. That is what religion can do. The ideal of all religions, all sects, is the same--the attaining of liberty, the cessation of misery.

Welcome to Vedanta Society of Japan

Branch of Ramakrishna Math and Mission

Welcome to Vedanta Society of Japan

Branch of Ramakrishna Math and Mission